De Pictura: Journeys Through Painting

Nathan Cohen

To cite this contribution:

Cohen, Nathan. ‘De Pictura: Journeys Through Painting.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/de-pictura-journeys-painting/.

I am an artist, and one of the ways I express ideas is through the medium of paint. I grew up in a family of artists, and so the experience of living with and looking at art has been with me from the start. As I have sought to discover what it is that I wish to explore, so I have come to realise that painting is a way of communicating that has been relevant for many, over a long time. At least, that is, perhaps until now. For in an ever increasingly digital age, we cannot make the same assumptions as in past generations, that people will continue to perceive the relevance of interacting directly with painting as a distinct form and as a means of expression.

In looking at the work of other artists, it seems to me that the act of making art offers a means to invent that can also leave traces of our journeys for others to learn from and enjoy. But a painting is a very particular construction that can be challenging to interpret.

I speak to you now through a different medium, that of words via a digital interface, and in addressing the question of validity as a subject, and in particular the validity of painting as an effective means of communication at this time, the thoughts I impart here are my own. They are born from time spent observing and reflecting on what I have seen and personally experienced, complemented by knowledge gained over the years through discourse with and contemplation of the views of others who have looked at paintings.

When I was invited to write this, I was intrigued by the challenge of addressing what is meant by validity in the context of what I do as an artist. One of the considerations it occurs to me is relevant is questioning the way in which we encounter paintings in a digital context, when compared with the experience of looking at paintings themselves. The digital is quite different to the physical tangibility of a painting. Yet this difference is now increasingly misperceived by the ready accessibility the internet offers, the pervasive nature of digital content in our lives, and with the ever-developing capabilities of virtual reality (VR) and haptic technologies.

I have taught in art schools for some time, and have seen many changes to the way in which artists explore different media to creatively advance ideas. I have also worked with digital media, including the use of computers in creating novel projection techniques in the making of interactive art installations, but always because these afforded me the ability to create artworks that could not have been created in any other way. Inventing with images in a digital context is a process I have found to be constructive. Where issues arise, it seems to me, is when digital platforms appear to change viewers’ behaviour more subliminally.

Choice and convenience are not the same things, and the seductive ability to reach for a tablet or smart phone to navigate through the world at large runs the risk of desensitizing us to the need to discover through personal experience and interaction with real objects and spaces. When I talk to an artist and the question arises if they have seen this or that artwork, and the response is that they have, but only on the web, I am left doubting if what we are talking to each other about can really be similar in terms of experience. A painting is more than just its visual form, and the experience of looking at paintings is different to that of interacting with a monitor or VR headset.

By taking the time to actually look at a painting we are, in some ways, validating the very purpose for which it was created, and in particular its comprehension is arrived at by encountering the form in which it is constructed (this can, of course, range from the miniature through to the architectonic in scale). Encouraging us to see the world differently through the creation of painting is an enabling act, one that requires of us time and patience in its interpretation – an experience that can establish a dynamic link with the architecture of our real-world space within which we interact with painting.

So, by way of a starting point, in addressing the question of why I feel painting is relevant in a digital age, I chose to look briefly at four paintings from earlier periods, that place the human being at the centre of our gaze. All of the paintings I refer to can be seen by visiting the National Gallery in London, a place I have been to many times in search of inspiration and reflection, and a home to many more paintings that offer all who take the time to visit the enjoyment of the experience of looking.

In my view, each artwork captures a moment in time and speaks of humanity through the intimacy of their subject matter and form – a validation of the human spirit in a dynamic world of change. When encountering the reality of these paintings I find that their existence as tangible forms are defined and reshaped in my imagination and in my memory of them. If as a result of reading this you may wish to question what is written and look closer at paintings to form your own opinion, then I hope that these thoughts may have served some purpose in encouraging this.

There is a space that we know of that we can imagine, and that also exists, but we can never see. It resides within each of us, and yet we need to apply our mind to comprehend it, and is a constant as we navigate our journey through the world around us.

*

Antonello da Messina, St Jerome in His Study, c. 1475. © Copyright The National Gallery, London 2017.

Antonello da Messina, St Jerome in His Study, c. 1475. © Copyright The National Gallery, London 2017.

In Antonello da Messina’s painting, St. Jerome sits contemplating a text he is reading, set within a mind like architecture. I look in, but always from the outside. His space is within. In searching this small painting, my eyes wander as the lion does through corridors that recede into different perspectives of the window framed landscapes beyond, as if looking through the eyes of the building. Above, birds alight silhouetted by the blue of the sky, their movements of flight and repose caught as saccade like moments in time.

The keys hang silently from a nail behind him supported by a structure that is encapsulated by the architecture that surrounds it. I am intrigued by the strange assemblage of objects, animals and birds, and wonder at their significance as they seem to impart a narrative that invites interpretation. There is a hidden geometry that places each form within its given space enabling the story to unfold. The painting is a construction by an artist who, despite the passing of centuries, has been able to create a form that leads me to ponder today what it is that is being depicted here, for without curiosity there would be no questioning, and without questioning there would be no intellectual pursuit.

The structure of this painting has intrigued me for many years, with its play between symmetry and asymmetry of space. Light is depicted in different ways, brightly illuminating the entrance, reflected within from the buildings surfaces, and framed as sky beyond. And all of this in a two-dimensional world that is an invention.

To create this illusion of space requires knowledge of these forms observed in reality, and as I have found, much experimentation with physical materials and the mastering of appropriate tools to enable this to be made. For a painter, these are prerequisites to create what we do and they form an important part of how we evolve our understanding of what we see and our ability to translate this into paintings where others can share in this experience.

While we live now in a different age, and the historical and cultural context that informed the creation of this artwork may have changed, it still speaks of ideas that we relate to today. The painting offers a virtual yet tangible space within which to wonder and to reflect, and it rewards our patience in contemplating what we see by discovering new dimensions within its intimate form.

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434. © Copyright The National Gallery, London 2017.

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434. © Copyright The National Gallery, London 2017.

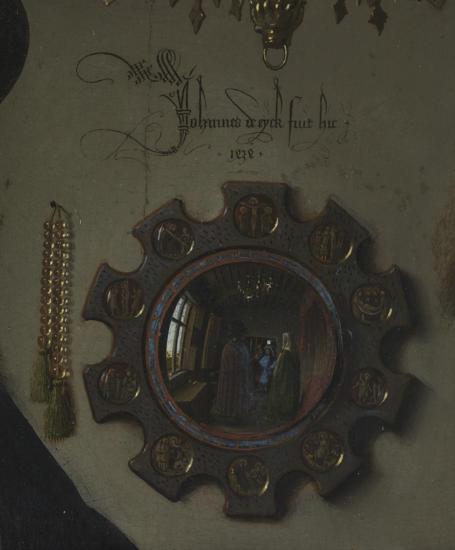

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, detail of mirror and rosary, 1434. © Copyright The National Gallery, London 2017.

The more I see, the more I question what I am looking at, and what relevance this may hold for others. Both the lens and the mirror refract and reflect light, as does a painting whose construction may consist of layers of colour upon a reflective background. The couple in the Arnolfini Portrait (1434) hold hands before the painter Jan van Eyck, and his reflection is to be found in the illusion of the mirror behind them. This plays with my understanding of where the paintings surface resides for while I know this to be an illusion, it is still possible to be convinced by the seeming reality of its construction.

Artists have explored different practical means to both comprehend and extend their observation including optical, mechanical and graphic instruments and the use of mathematics, geometry, and proportion to construct images. Painting is essentially abstract, whether seeking to represent a likeness of things seen or imagined. I am intrigued by the play with spatial expectation to be found in many works of art that explore the encounter between the second and third dimensions, and I also make paintings which explore the inventive possibilities of constructions that are ambiguous in their spatial interpretation.

In questioning what I see when looking at this painting, I am also reaffirming my comprehension of the reality of the space I actually exist within. I sense that I am looking at an illusion, and where this meets the reality of my physical world I derive pleasure from the experience, a reward for the intellectual engagement of seeking to ‘resolve’ this intriguing spatial conundrum.

*

Johannes Vermeer, A Young Woman Standing at a Virginal, c. 1670–72. © Copyright The National Gallery, London 2017.

Light filters through the window illuminating a room and its contents. References to a world outside can be seen in the landscape painted on the instrument lid that mirrors the window at the left of the painting, and in the picture that hangs high on the wall behind – a reminder that this interior is part of a larger world. A chair awaits and she looks toward you, her hands resting on the keyboard of the virginal.

I stand in front of the painting in a space that has been created for it, but that is quite different to the space in which it was conceived, or for which it may have been intended. And yet the painting is sufficiently self-contained to be readable in a variety of spaces and contexts.

A painting is an immersive experience, where at its best the image draws us in and allows us, if momentarily, to become one with the space within the image. When I later recall this painting in my mind, I am not particularly conscious of the specific place in which it is currently located, yet my memory is formed in relation to the experience of having seen the painting as an extension of the space in which I observed it, a process that enables me to comprehend that image in the way I imagine the painter intended, and its reality as an object forms an integral part of this experience. There is a real surface onto which paint has been applied, and I can relate to this in a way that is quite different to ‘seeing’ it on the computer screen.

In contrast to my experience of witnessing St. Jerome, I am invited to be a part of this scene and the painting’s composition suggests I am present as a participant. The three-dimensional properties of the space are depicted in the geometries of this painting, a dialogue between the architecture and furniture and the viewer and the viewed. In this moment of encounter I feel as if welcomed into the painting both by its subject and its construction.

Where there is detail so there is also questioning of what I really see, the surfaces dissolving into flecks and dots of colour as I approach to inspect more closely. This is most clear in the depiction of the human form, the face and hands appearing almost out of focus in comparison with the other surfaces in the painting, as if in an early photograph where movement blurs the image during a long exposure.

The question of where to locate focus is significant in the composition of an image, for in the choice the painter articulates intention. There may be one or many foci, and they offer a means to comprehend what is depicted and how the space within the painting can be interpreted.

I bring my own perspective, both literally and in terms of experience. I project my own thoughts upon what I see in a painting, and seek to compare and relate the visual sensation to memories of other things seen and felt. This is a multi-layered process, which can stimulate associations across time and place, the painting providing a catalyst for the imagination.

*

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self Portrait at the Age of 63, 1669. © Copyright The National Gallery, London 2017.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self Portrait at the Age of 63, 1669. © Copyright The National Gallery, London 2017.

The sitter’s eyes meet mine in Rembrandt’s self portrait of 1669 – the year of his death – in which I experience a direct encounter with the artist himself. Except, he would have been examining his reflection in a mirror to make this painting, and I am seeing him as he would be seen by himself.

The light that pervades the canvas suggests an internal space, the shadows capturing the luminosity that bathes the head of the artist rendering the rest of his form as if slipping quietly into the embrace of an encroaching darkness. The intense blackness of the eyes invites me to contemplate an inner space, one which we all may be aware of but must spend our lives to fully comprehend. To me this appears as a moment of self awareness and doubt.

I find this to be a very personal and revealing painting, a work of art that is disarmingly honest in its apparent intention. Paint on canvas is visceral. The very nature of the medium is fluid and yet the slow ‘drying’ of oil paint suggests that this painting would probably have been painted over a period of time. Thick impasto paint gradually flattens with the years, cracks appear, and the painting reveals Rembrandt’s way of building it as the paint becomes increasingly transparent. When I stand in front of the painting, I am aware of how its physical condition reflects the aging process of its creator, and that I am now able to gaze upon it in this moment of its existence, as the painting itself changes subtly with time.

The artist as subject offers insight into the creators’ mind but also presents me with the challenge of truly comprehending what I see. At one level, it is a painting of another person and, yet, the intimacy invited by the immediacy of contact invites a more personal emotional response. I begin to wonder what it is that he sees as he looks upon himself, what he wishes to impart by creating this painting, and this encourages me to look closer, and reflect more deeply on the experience of what I have seen.

For an artist, there is always the next painting to be painted that continues the journey and there is the sense that there is never enough time, but in the act of pushing the boulder each time to the top of the mountain there are the moments of completion that validate the effort made. In this painting, we are offered a rare moment of communion with one who has lived that experience and who, still now, can share this with us as we live ours.