The Cleaner, the Saint and the Hermit Crab: On The Source, Llandudno, June – July 2016

Sarah Younan

To cite this contribution:

Younan, Sarah. ‘The Cleaner, the Saint and the Hermit Crab: On The Source, Llandudno, June – July 2016.’ In response to Joey Bryniarska and Martin Westwood, ‘On/Off-Message,’ OAR Issue 1 (2017). OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 1 (2017), http://oarplatform.com/cleaner-saint-hermit-crab-source-llandundo/.

The Source was performed by Sarah Younan in the Tabernacle Chapel, Llandudno, between 13 July and 3 June 2016. During this time, Sarah Younan, as the cleaner, administered to the chapel and the local community daily from 5 in the morning until 8 in the evening. The cleaner, a ritual cleaning nun, wore a habit and practiced abstinence and chastity; she remained enclosed in the chapel and dedicated herself only to the observance of ritual: the purification of the site, herself, and others.

In the Tabernacle Chapel dust covers all surfaces, Welsh hymn books and bibles are heaped in a corner, spider webs, wood lice, dead flies. The cleaner opens the trap doors that cover the sunken baptism receptacle one by one. Hand painted words are revealed; ‘Un Arglwydd, Un Ffydd, Un Bedydd’ / ‘One Lord, One Faith, One Baptism’.

She begins to clean.

If, as Mary Douglas argues in Purity and Danger,¹ dirt can be defined as matter that is out of place, then cleaning is a culturally defined, ritual action. Following this definition, for matter to become dirt, a space must exist within which matter can be out of place. The Tabernacle chapel is such a man-made and designated space. As a chapel, it possesses religious and ritual qualities in addition to its physical characteristics. It is a liminal space, within which cleaning is transformed into a spiritual and sacral action. Already, cleaning can be seen as connected with spirituality and religion. ‘Cleanliness is next to Godliness’ is a well-known trope. Traditionally, women have volunteered as church cleaners.

As the cleaner dusts and sweeps, the former congregation of the church swirls through the air around her, settles in her pores, is breathed deeply into her lungs. Her squeamishness fades, she is no longer too proud to touch; dirt is only matter, which is out of place. The cleaner picks up dead insects, buttons and coins. She throws nothing away but sifts through the dirt, finds meaning in the debris. She collects the dust and preserves it in transparent sheets of wax. Entrance hallway: dry leaves, dust grit. Central pews: hair, coins, confetti.

All processes produce pollution. Dead skin cells and hair fall from our bodies, wasting away in a permanent shower of debris. Outside, I light a smoke. The pollutants I breathe travel through my body and deposit as layers in my skin, hair, teeth, bones. I age, constantly shedding bits. A hair detaches and falls to the ground. Past lovers stroke my hair and kissed my skin, but the hair and dead cells under the church pews are no longer lovable. Detached and out of place, they become a reminder of mortality. To dust you will return to dust you will return, to dust you will return. Perhaps hoarding is an act of love, every tedious little moment and thing too precious to waste. Box it up, hold it, keep the relics of your minutes and seconds; there will be no time to go back and revisit these memories, but just to have them there, present in those material traces, in the debris and dirt, gives comfort.

A visitor recognises the sparkly snowflakes in the dustpan; ‘this is from a Christmas workshop, I was pregnant at the time.’ Another woman finds a connection: ‘They had a Santa here. My son was just about to turn twelve and this was the last time I took him to see Santa.’

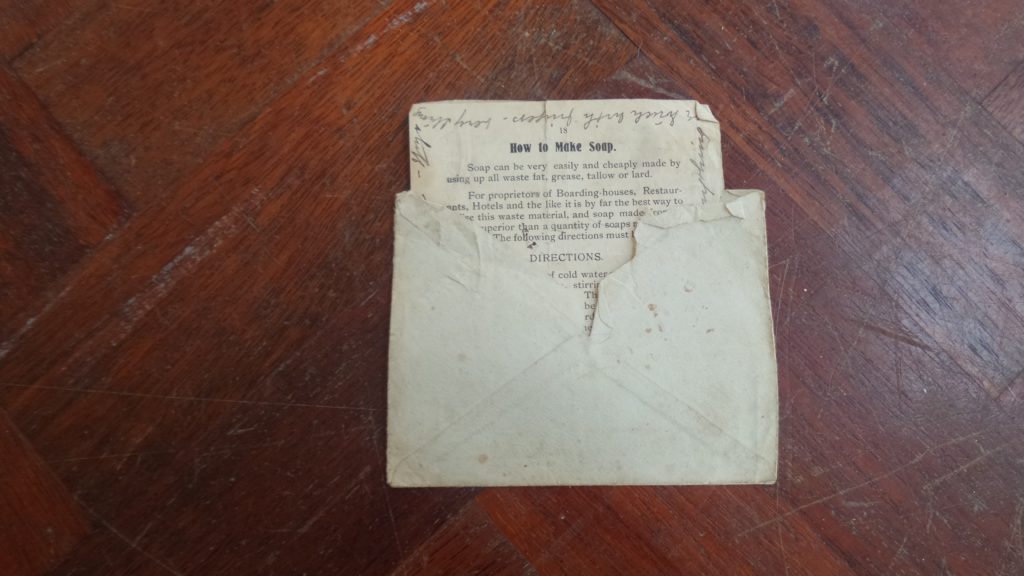

The cleaner prepares soap in the vestry: caustic soda, some lavender oil, lard. Pork fat, rendered white and odourless. An animal sacrifice. She washes and mops the Tabernacle with this soap. In the evenings, she carves bones from the white blocks.

The local museum holds the incomplete skeleton of a Bronze Age female, Blodwen. Found in a cave on the Little Orm, half an hour walk from the chapel, surrounded by pig bones. I decide Blodwen was rendering lard into soap. She was a cleaner, the first. Blodwen recognised the need to create an empty slate; she used soap to scrub the stones of this holy site – remove all traces and stains. The space set apart from the natural environment, spotless, clean, baptised. Blodwen a saint, the Tabernacle a holy site of cleaning. Scrubbing pews all day can send you loopy.

A saint carved from soap. A holy woman, the world’s first cleaner. The cleaner lays her saint out in the vestry, she is setting up a museum. Next to the holy bones, dead insects and lost things fill the glass cases.

People have begun to visit more often now. Some return again and again. They bring both life and pollution into the chapel; their feet carry in the dirt from the street. Cleanliness is an on going process, not an attainable state, and so the cleaner tends to her visitors and, when they leave, she cleans up after them. Some have their feet washed. They speak about their tarnishes and stains to her. ‘I used to rip out the nails of my little toes until they bled.’ ‘My nan never let me wash her feet; towards the end, when she was very ill, she let me do that for her. I think it helped her pass.’ ‘My late wife used to cut my toenails. I find it hard to reach them myself.’ They leave, perhaps, a little lighter on their feet.

Cleaning is also an action without permanent outcome; dust has a tendency to creep back in. I tell myself not to notice how my visitors carry dirt from the outside into my sacred space. Yes, mine. I cleaned it. Carpal tunnel syndrome from all the scrubbing sends a shock through my wrist. This space is mine, I earned it. Maybe I have found a home. A couple of my guests carry in the news; Brexit, a Great Kingdom again splendid in its isolation. Secretly, I loathe them. Me, the immigrant, the cleaner, the other cleaning their church. The caretaker has no claim to the space. I am nothing but a crab, a hermit crab carrying this lumpy chapel with me for comfort and shelter.

One lady hopes a foot-washing will help her arthritis. ‘I am no healer’, the cleaner wants to say, ‘not even a real nun’. But she has crept too far into the shell of the chapel. Like a hermit crab, she now bears its weight. The cleaner and the chapel form a symbiotic relationship. She has started to dream of the church, the smell of turpentine, the things she finds in the dust. She is the ‘other’ that cleans to keep the chaos, the dirt, decay and disorder at bay. Cleanliness next to Godliness: a sweeping hermit. Saintly, perhaps.

Dirt creeps back in, the work of the cleaner is never done. Perhaps a completely sealed vacuum could remain forever clean, but this would be a dead and infertile realm. Pollution, both physical and metaphysical, is necessary for new mental and physical states to arise. Cleaning is one of the actions, which creates symbolic and liminal spaces and imposes man-made order on the physical world. And yet, this order needs to remain brittle and corruptible, or else we would enter into frozen, infertile, dead spaces.

The cleaner sweeps the edges of our man-made world.

All photographs are by Sarah Younan. A video was made about the project, and may be accessed here.

1. Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger (New York: Routledge, 1966).