Setting Out

Anita Paz

To cite this contribution:

Paz, Anita. ‘Setting Out.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 0 (2016), http://www.oarplatform.com/setting-out/.

I want to capture certain moments of thinking as if they were just points from where I might have set out.

– Adrian Rifkin, 2015

A response, according to its commonly accepted definition, is the offering of something in reaction to something else. A response may take the form of a written contemplation, an inter-medial conversion, a spontaneous utterance, an archival exploration, a burst of movement, a change of disposition, a creative reflection, or a metatextual, intratextual or intertextual translation. It may also take no form at all, manifesting itself as loud silence, or still tension. Equally, the something to which the response is reacting may take many and no form, exist in all media and none, and perform different roles or no role at all. In any and all of these cases, the response is a form of thinking (verbal or visual, loud or mute, expanding or static) that comes as a reaction to another moment of thought. The response is an act of generosity that follows a provocation – an act, that in reacting to the thought that provoked it, is setting out from it.

Setting out from a found – or better yet, ‘captured’ – moment of thinking is a will expressed by Adrian Rifkin in the closing notes of ‘Dancing Years, or Writing as a Way Out’ (2009). ‘I want to capture certain moments of thinking as if they were just points from where I might have set out’, he writes. This will to set out is therefore both the moment of thinking from which I wish to set out in my response, and the methodological approach my response will assume, in being a response. Setting out is understood here as a departure, a journey that has its initiation at ‘certain moments of thinking’ – someone else’s thoughts, someone else’s words, and its trajectory directed towards what these other thoughts, what these other words, could say.

A response is a setting out. It begins with a statement, one that is taken as a mark, distilled into a starting point, from which departure takes place. Being a departure, a reaction that is a response is not only ‘to’, but also, and necessarily, ‘from’. It responds to a moment of thinking, and within that, it departs from it. The response is ‘to’ and ‘from’, and those are the two potencies inherent in it. It sets out between ‘to’ and ‘from’, from the ‘to’ to the ‘from’, from the ‘from’ to the ‘to – two rejecting poles that set it in an alternating motion. Oscillating between the contradictory directions of ‘to’ and ‘from’, and existing within the dichotomy of being simultaneously ‘towards’ and ‘out of’, the mode of the response assumes and inhabits a schema: that of the helix.

This helical schema of the response is precisely not a Hegelian dialectic helix: its progression is neither through tension nor towards a synthesis-based resolution. Nor is it a full-circle cyclical movement like that of Nietzschean eternal recurrence: the rotundity of its movement does not draw an aura-like nimbus around the moment of thinking, and iteration is not its mark. Instead, the throwback between ‘to’ and ‘from’ creates a vortex, within which ‘to’ and ‘from’ draw closer together, while continuing to push apart, charging the existing tension.

The tension of the departure is central to the ontology of the response. A reaction that is only ‘to’ is nothing but an opaque reading, understood here as a private act of processing. It may be an examination, a commentary or an impression, but it will always be conditioned by the disposition of the reacting subject projected towards the moment of thinking, so that the latter becomes a mere platform. On the other hand, a reaction that is only ‘from’ is nothing but an empty affirmation, understood here as a public act of ratification. The reaction ‘from’ is a derivation. It moves d’après – according to the moment of thinking, and necessarily after it, following it, so that it is conditioned by its grounding in the moment of thinking, while the very words of the thought become roots that feed it. A reaction that is only ’to’ is often disingenuous, a deceitful usage of the thing itself. A reaction that is only ‘from’ risks the habit of ontological gerrymandering – the redefining of the boundaries of what is interesting or problematic in or around the thing itself, so that it serves the purpose of the reaction.

At the same time, this does not exclude the possibility of the response being either a reading or an affirmation. If the response is to be understood as reading, then it is to be understood as reading of what was meant instead of what was said (in a Heideggerian, or post-Heideggerian manner), or even as reading what has never been said (like a Benjaminian image of the past that flashes up and becomes what it has never been before). It is not a question of illustration or clarification, but of imagination and invention. If the response is to be considered a reading, then it is not as a weak interpretation, but as a forceful interference. Similarly, understood as affirmation, the response will be a declaration that not only comes out of the moment of thinking, but necessarily states and declares something to it, allowing for the tension of departure to build.

To depart is understood here using two of its etymological meanings, the Old French ‘départir’, ‘to set oneself apart’, and Late Latin ‘departire’, ‘to divide’. The response as a departure also has this dual mode: in part, it is a movement outwards, in part, it is a split. In being a movement outwards, setting itself apart, the response is a setting out that is also a breaking out – out of the meanings enclosed and delineated within the statement, and out of the field of signification framed by the stated. This is not deconstruction understood as liberation from meaning through an infinite expanding of an unbound context. Breaking out might take down walls, but only to use the debris towards building up annexes. In its movement, the response breaks out from within the moment of thinking, and creates a new – equally enclosed, delineated and framed – moment. The response is a movement that breaks through thought, creating thought out of thought, cogitatio ex cogitato – a thought out of what was already thought, but also cogitatio excogitata – an invented thought.

The movement of the response is a dynamic force introduced into – or, better yet, forced upon – a moment of thinking. A moment of thinking may only be captured and distilled into a starting point, after it has taken its final form: a form that may never be singular. Responding to a written thought, the form of the assumed starting point is, at least, both verbal (in being a sequence of specific words chosen to communicate that thought), and visual (in having those words exist as a mark of ink on the paper). Responding to a performed gesture, that form is, at least, both visual (in being a mark the body left in space), and audial (in having that gesture generate a certain noise in that space). Although this second instance may be deemed as inherently non-static (a movement), I claim that a response reacts and forces itself upon an iteration of that movement, or a plurality of such iterations, that are, in and of themselves, static: from the moment they were performed, they took form – one that is permanent. Appearing in its plurality of forms – verbal, visual, audial and other – the moment of thinking is a static instance: responding to it, creating a movement from the inside out is animating what would have otherwise rested in stasis.

The departure of the response is a movement that projects from the inside out, while it itself is a dynamic force penetrating the moment of thinking from the outside. Being extrinsic to the thought, it nonetheless situates itself on the inside of it, where it initiates a movement from within. The response comes from outside, but has its true beginning in the moment of setting itself apart – moving – from the inside. In that, it collapses the extraneous and foreign into the inner space of the thought, allowing it to dwell and permeate it through, pushing that very inwardness outwards. The response as a movement is a destabilising force.

The second mode of the response as departure is that of the split. In being a split, it is a violent breakage from its point of origin, a forceful division. Thoughts survive in trajectories – they survive as trajectories. Projecting down a course not only temporal, but also geographic, they become traditions, solidify as canons or slowly dissolve down the line. The response to a moment of thought opens up a new trajectory – it creates a duality, a bifurcation, a path that is yet to be taken: departure as deviation. The response separates, divides itself from the moment of thinking. More than a coexistence, it gives place to a shared existence, seeing that harmony and accord are rarely maintained.

Working from the moment of thinking outwards, the response is a split in as much as it divides its course from that of the thought. Directed inwards, the response is also a split – a violent crack – from within. Permeating the inner construction of the thought, the response creates divisions within its reasoning. It breaks down the thinking of the thought, opening cavities between its elements, and pulling outwards that which it can consume for its own purpose. The response sets out from the point created out of the moment of thought, a point it fractures in order to extract from it its own building blocks.

Within both of its modes – of the movement and of the split – the response performs the stated – a setting out, a departure – while the moment of thinking itself leans towards a new thought. As a mode, the departure of the response ports within it certain moments from which and to which new thoughts come to be. Instances vary. One thinks of Derrida’s Kantian parergon – fractured from its moment of thinking, the concept is transported from one philosophical context to another, expanding, giving place to a new thought. Philosophy responds to philosophy, but also to visual culture. Think of Foucault’s Magrittian pipe – a departure from painted object and text towards a discussion around representation and deixis in the calligram. From Foucault there is also the famous response to Velazquez’s Las Meninas, a painting out of which and to which many responses, many new thoughts have come about, not least Picasso’s Velazquezian maids of honour, a visual response where reiteration guided by willful forgetfulness becomes the site of inventive departure (and Las Meninas becomes ‘mis Meninas’ – my Meninas). Kandinsky’s Schoenbergian concert also comes to mind: through the mode of departure, a musical performance on the Monday of 2 January 1911 becomes Impression III (Concert) – colour responds to an asymphonic score. Staying within the realm of music, Philip Glass’s Kafkaesque trial is a recent example – responding to the novel is an opera that ports in it a moment of thought split and set in motion, so that it becomes something else entirely.

At the same time, and on a second register, the departure of the response is not only its mode, but also its means, marked by partition: a separation between the moment of thinking and that of the response. Departing from the moment of thinking, the response gives place to another moment of thinking, marking itself against the first one. Re-photographing the great American West after Timothy H. O’Sullivan is not only departing from within it and moving back to it, it is also marking itself as a separate moment, one that comes out of the moment of thinking, but that is not a part of it. Boris Eifman’s praised choreography of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina activates the latter, while setting itself apart: proposing a new interpretation of the character’s moral conduct and rupturing the assumptions of the reader (turned viewer), it comes out of the written text, while at the same time leaving it behind, offering a new vision. Similarly, Arthur Pita’s ballet of Metamorphosis is not just an adaption of Kafka’s novel, just like Claire Denis’ film L’intrus is not an adaptation of Jean-Luc Nancy’s eponymous text, and the latter’s curatorial project ‘The Other Portrait’ is not merely an adaptation or a continuation of his own essay ‘The Ground of the Image’. An adaptation is a derivative reaction ‘from’ that involves inter-medial translation, but these are all responses, departures: moving ‘to’, they do not simply interpret, but also interfere – a ‘to’ that is ‘from’; moving ‘from’, they do not simply derive, but also deviate – a ‘from’ that is ‘to’.

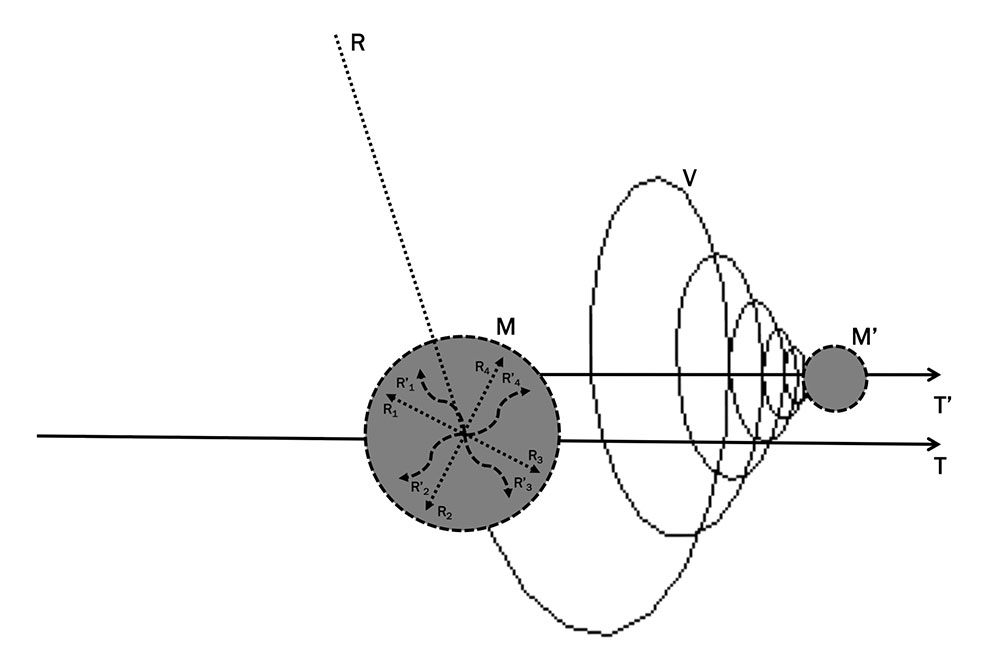

Figure 1. The response (R) is a dynamic force forced upon a moment of thought (M), that exists in the world on a certain trajectory (T). Penetrating the moment of thought from the outside, it moves on its inside (R1–R4), collapsing the extraneous and foreign into the inner space of the thought, allowing it to dwell and permeate it through, pushing that very inwardness outwards. The response is also a violent crack from within (R’1–R’4), one that breaks down the thinking of the thought, opening cavities between its elements, and pulling outwards that which it can consume for its own purpose. The movement the response is that of the vortex (V), so that ‘to’ and ‘from’ draw closer together, while continuing to push apart, charging the existing tension. The response to a moment of thought opens up a new trajectory: dividing itself from the moment of thinking (M), the response creates a new, equally enclosed, delineated and framed, moment (M’). That new moment (M’) moves along a new trajectory (T’).

A response – reaction by means and in the mode of departure – is an effective reaction. This is not to say that other types of reactions are ineffective; it is only to say that they are not effective as reactions. The already mentioned reading as interpretation, for instance, might be effective as a form of analysis. However, it is ineffective as a reaction, because for a reaction to be effective it must activate – indeed, reactivate – the moment of thinking, generating movement and destabilising its static form: it must give place to a new thought.

If responses are effective reactions, it remains to ask what makes an effective response. Or, better yet, what makes an affective response, for a response is effective for its disturbance, for the affect it emits. I shall answer this with a digression.

Originally, I meant to respond to Rifkin’s text through an entirely different moment of thinking. On the very first page of ‘Dancing Years, or Writing as a Way Out’, he writes: ‘I decided that it was an interesting departure to make things up’. I did not know how to react to it, but I knew I wanted my reaction to be a response, and that within that I wanted to unfold response as such. Both moments – the one on the first page I just mentioned, and the one on the last I ended up using (‘I want to capture certain moments of thinking as if they were just points from where I might have set out’) – led to the same movement, to the same split. Both equally allowed me to move to and from them, to destabilise them, to set out from them, and to depart, making things up (a new thought). But I made my choice, and it was the latter quote. I did not choose it because it was more effective for my response – further into (both logically and chronologically) Rifkin’s text, thus allowing a greater spanning outwards, and greater tension. In fact, I did not choose it at all – instead, I un-chose the first one. That was because in addition to a response around responses, that first moment of thinking – ‘I decided that it was an interesting departure to make things up’ – seemed to elicit further responses: it departed towards art history as a discipline, towards questions of invention and lying, and towards speculations around truth and truthfulness. And this further response seemed to me to go much further in relation to Rifkin’s moment of thinking – so it had to be un-chosen, reserved for a future moment, when it could receive a better response.

Moments of thinking may be activated in more than one way. That is to say, moments of thinking may lead to more than one effective reaction – to more than one response. But what makes a response to a particular moment of thinking affective is the amount of disturbance it ejects into that moment: the further it pushes the moment of thinking, and the less stable it leaves it, the more affective it is.

Rifkin’s words around capturing moments of thought like points from where to set out are what stimulated this response. It was the words, not the context in which they were uttered, or the intention, that gave them place. The words themselves – someone else’s thoughts, someone else’s words – became my point of setting out, where setting out is responding.

About the author:

Anita Paz is an Oxford-Dowding scholar at the Ruskin School of Art, University of Oxford, working on art theory and philosophy. Her most recent publication appears in Philosophy of Photography, and a publication on Thinking Images co-edited by her is forthcoming in 2018. Anita is a co-founder and editor of OAR.