Is this the End? Or Is it a Beginning?

Florian Dombois and Michael Hiltbrunner

To cite this contribution:

Dombois, Florian and Michael Hiltbrunner. ‘Is this the end? Or is it a beginning?’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 3 (2019), http://www.oarplatform.com/is-this-the-end-or-is-it-a-beginning/.

Michael Hiltbrunner: How did you get involved in artistic research? What did the arts look like at the time? And why was this idea of artistic research attractive for you?

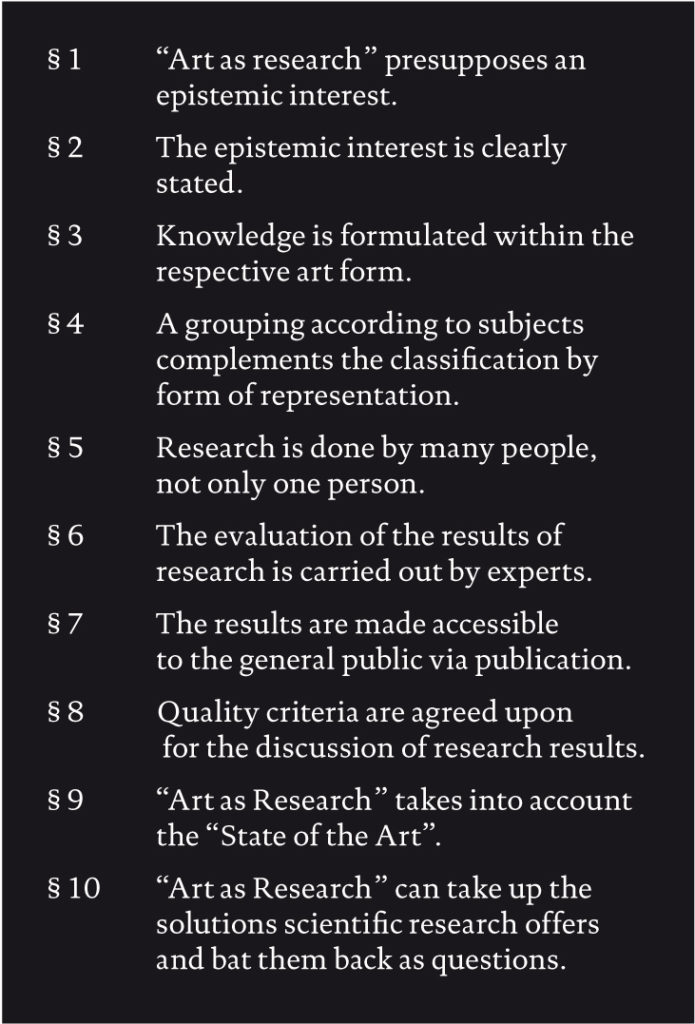

Florian Dombois: What kind of artistic research do you mean? I am not sure if there is only one single kind of artistic research. If you mean how I became interested in speaking of ‘research’ in the context of art, and of ‘art’ in the context of scientific research, then I can tell you a story. It is a long story, but I will keep it short. There are some interesting parallels between artistic and scientific practices, even though I don’t see them as sisters. One we have known for 500 years, the other for 40,000 years. In family terms I think you could call science an ill-mannered daughter of art.1 And I like to provoke myself and others to think. Claiming that art does research provoked most scientists enormously – and very often still does. And yet I love to tease them, as they very often cling to the belief that only science holds the truth. This debate can become quite agitated, for instance, when one points to the limits of science, especially when using artistic terminology. I studied geophysics between 1986 and 1992 and very often provoked my fellow students with questions about, or truth claims for, art. As I was good at mathematics but grew up in the art world in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, I soon developed an affinity for both worlds. Besides provoking, I detected a number of poetic ideas, approaches and installations in the world of science that I could hardly share with anyone. So I built up a body of unseen work instead, exploring poetic spaces in mostly scientific surroundings. In 2003, I was asked to develop an interdisciplinary institute at the newly established Bern University of the Arts. The idea was to bring together students from theatre, music, design, fine arts, etc. Since I distrust(ed) the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk (‘total work of art’) and opera because of their strong hierarchical organisation, I suggested calling every student a researcher instead, to ensure they could meet eye to eye. The students on my programme had to work in what we called verschärfte Nachbarschaft (“enforced neighbourhood”). This enabled them to watch each other while working, as well as steal, copy and pervert each other’s strategies, and then channel this experience into their own artistic practice. I called it “art as research” as I wanted to nurture a sense of collaboration about developing art, not about the product. Initially, all was well. But then I realised that my claim – ‘art as research’ – was provoking my fellow art professors. I realised that at a time during which everybody assumed that scandals in art were a matter of the past, we could have heated debates about what art is – or rather about what art is not. This was a great prospect. Thus, in 2006, for example, I wrote a manifesto comprising 10 commandments.

Florian Dombois, Manifesto, 2006.

Florian Dombois, Manifesto, 2006.

The biblical number was intentional. It created wonderful and fruitful tohu wa-bohu,2 even on an international level.

Michael Hiltbrunner: I remember you as one of the co-founders, or even as the founder, of SAR, the Society for Artistic Research. How did this happen? What were the goals? When and how were the later Journal of Artistic Research (JAR) and the Research Catalogue (RC) founded?

Florian Dombois: Well, one of the limitations of the research done in the humanities and in the natural sciences is that it ends up in a written publication. Now if the medium of thought influences what we think and what we can think, then changing the medium of publication can have a great effect. I have always wanted to test this assumption. What happens if we break the dominance of the written word and allow sound or film to be the backbone of (scientific) thinking? Can we flip the status of media as the mere illustration of a text into its opposite? What kind of science would that be that arranges its thoughts around film or sound or images? The shift from book rolls to codices to printing – the so-called ‘Gutenberg Revolution’ – fundamentally transformed our knowledge cultures. Against this background, I came up with the idea for a Journal XXL, as I called it. Then, in 2008, I met Michael Schwab. He had similar ideas, so we both developed a concept for the JAR and the RC. I wanted a publication format that would allow for an opposite hierarchy of media: non-verbal first, verbal second.

Florian Dombois, Image for the founding of JAR, 2009.

Florian Dombois, Image for the founding of JAR, 2009.

Michael Hiltbrunner: And what role would an artist have in this context? I also remember that you left the SAR board after a while, also on account of your role and work as an artist?

Florian Dombois: I feel at home in the non-verbal. So I thought that I might help to develop new formats of expression and new articulations of thought in the digital. After a while, however, I realised that my artistic contributions and concerns were not shared. Many people at the JAR and SAR are great intellectuals, very much at home in verbal thinking. But for me, this was not enough. Poetic spaces were rare or, if they existed, they were flooded in words. Even here and now – what are we both doing? We are talking…

Florian Dombois, The foundational meeting of the Society for Artistic Research, Bern, 2010 Note: The Swiss artist Manuel Burgener, commissioned by Dombois, built a huge pole from fresh wood, which smelled strongly of resin and which also interfered with the projection. Tellingly, not one of the eighty present artists and directors took note of it.

Florian Dombois, The foundational meeting of the Society for Artistic Research, Bern, 2010 Note: The Swiss artist Manuel Burgener, commissioned by Dombois, built a huge pole from fresh wood, which smelled strongly of resin and which also interfered with the projection. Tellingly, not one of the eighty present artists and directors took note of it.

Michael Hiltbrunner: How did you encounter the development of artistic research at the time? How did the field change? What was your position in it? What did you make of it?

Florian Dombois: I am not a historian. I remember that claiming art as research in 2002 was new in Bern. Apparently, my approach was also new in Switzerland, and fresh on the international level, or at least I was told so. And I could feel it from the reactions I got, especially in 2006, when I launched the manifesto and distributed it in talks, happenings and podia in Bern Kunsthalle, Zurich Shedhalle, Berlin Walter Benjamin congress, Galerie Rachel Haferkamp (Cologne), Amsterdam International Conference Society for Literature, Science, and the Arts, London International Conference for Auditory Display and University College and so on, discussing it with people such as Elena Filipovic, Philippe Pirotte, Win Van den Abbeele et al. In the following year it was discussed in Karlsruhe Art Academy, Lucerne Music Academy, Basel University, Manchester Tuesday Talks, Annecy Conference Experimenta at the Art Academy (who translated and published my manifesto in French), PACT in Essen or also Madrid during Art Contemporary (ARCO) where I shared my thoughts with Chuz Martinez, Pavel Büchler or Jesus Fuenmayor, who were all on the same panel about group exhibitions. For example, I remember that Chuz had not thought about research at all. Ah, there was also The Madrid Trial happening at the same time, where Anton Vidokle and Tirdad Zolghadr staged their ruined manifesta. There was Jan Verwoert as judge, Vasif Kortun and Chuz Martinez as prosecutors and Charles Esche as defense with lots of fancy art world witnesses such as Maria Lind, Liam Gillick and Anselm Franke. So fancy and so boring! You have to watch their documentation video, it feels dead. I was coming from art production, from interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary exchange among artists. Whereas institutional and political reasons were fuelling the Swiss and the international debate. So I was drawn into the debate and sparked to life some fires here and there. But fighting institutional dynamics becomes boring, because you can’t win, and because your audience consists mostly of bureaucrats. So after I had enough fun, I stopped the game of calling art a form of research.

Michael Hiltbrunner: For many involved in artistic research it is a valuable alternative to an art system focused on products and individual careers, as artistic research should build on a critical tradition, work with groups, teams, collectives, move away from the artist as an isolated genius or entrepreneur, and turn him or her into a specialist for image production in a broader sense, and thus once again into an artist.

Florian Dombois: I don’t completely agree. Many art collectives and very critical artists are successful in the market. But I share your hope, that research environments could nurture other forms of criticality and cooperation. Nevertheless, the two main tricks that I would like to steal from the scientific research funding are: (a) to be paid by effort, for the time spent, not for the product; (b) to allow peers to decide where the money goes. In essence, mathematicians decide for mathematics, not the historians of mathematics, nor the collectors, nor the critics. You need to be able to produce good mathematics, or keep your mouth shut. Oh, sometimes I dream about what art would be like if not everybody thought they knew better…. er?

Michael Hiltbrunner: Do you see that team spirit in artistic research? What culture has been established, also with research funding? You built up a research group in Zurich? How is this work developing?

Florian Dombois: Uff, so many questions. Okay, let me try to answer each in turn. I mentioned enforced neighbourhood earlier on. I don’t think that art as research automatically means that you make art as a collective. I mean, scientists also publish individually after exchanging ideas with their colleagues. You might share a laboratory, use data from others for your own work, you discuss, you challenge each other, locally but also internationally. Throughout, however, you remain responsible for your published claims. And as far as I know, Michael, you aren’t publishing your books or essays as collective, are you? I just received an publicity mail for you with all your books and name on the front page, ha ha ha. And for me this is ok, as I see authorship not naively. ‘If you believe to have a new idea, it means only you haven’t read enough.’ As Alexander Demandt used to say to us. And this is absolutely right. So putting your name on something means to me also to risk counter-action, aggression, misunderstanding. And I am experiencing it with the research terminology. I think most of the people still don’t get what I mean and am interested in. Anyway, once I realised that the institutional interest in artistic research is simply about being able to say ‘we are doing research’, I thought, right, I can offer this, too. Unlike in Bern, where I’m now (in Zurich), this will not be a game of undermining our ideas about art, but instead a very pragmatic and strategic venture. If research serves to develop a discipline, then we need (a kind of) research that develops the arts. Besides, we only want peers, i.e., experts in the making of art, to decide on funding. I don’t want to talk about art. I want to open poetic spaces. I want to experiment with new forms. I believe in the “truth” of art, because it is not simple.

Michael Hiltbrunner: How does the critical culture of academia encounter that of artists at an arts university? You insist on artistic research helping the artist and the field of art. What might this look like in practice? What is the role of those in the field (like myself) who are not working primarily as artists? What do you think about ‘us’, academics from other disciplines working in and close to artistic research?

Florian Dombois: I am not sure who ‘you’ are. What is clear to me, however, is that art schools and their research units should focus on the making of art. This is our duty. What does making art require? How can research support the process of making art? The dividing line is not between artists and non-artists – if we look at large studios such as those of Eliasson or Koons, which also involve non-artists in the production process.3 For me, the question is if ‘you’ merely look at art and artists and don’t contribute to the making, and if ‘you’ remain in the comfort zone of watching others trying to make new works: Well, then, ‘you’ had better work in academia, e.g., in an art history department. So it’s less about ‘your’ identity or disciplinary background, but about what exactly is your concern? Who do you want to support? Who are your peers, who needs your work and who will make use of it?

Michael Hiltbrunner: Your Venice project was an artistic research project. You had decided to produce a solo work within the research field. What made you break with the research tradition of collectives and move into a solo work again? Why did you do this within the research field?

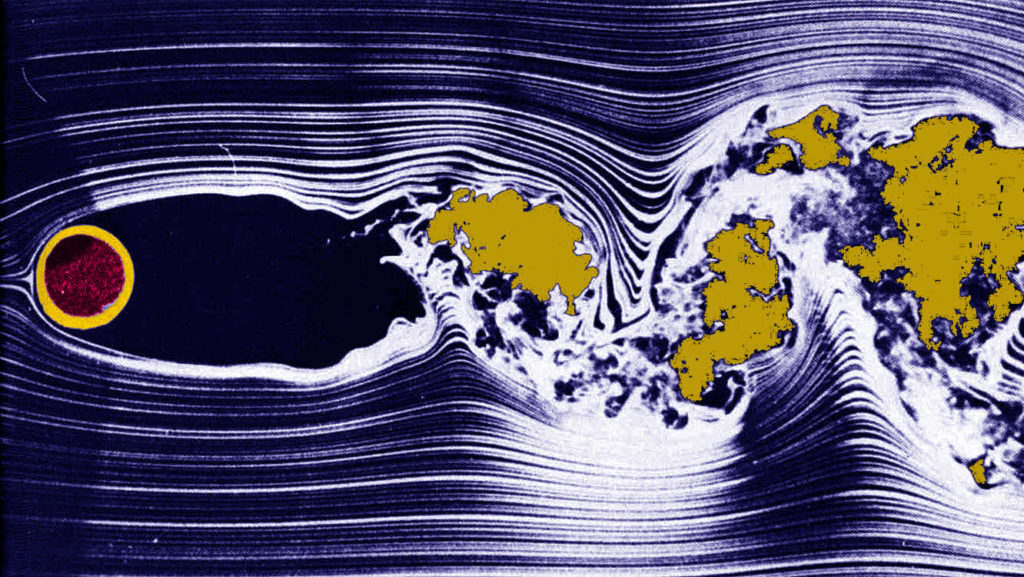

Thomas Corke and Hassan Nagib, manipulated by Florian Dombois, Publicity image for Venice Research Pavilion, 2017.

Thomas Corke and Hassan Nagib, manipulated by Florian Dombois, Publicity image for Venice Research Pavilion, 2017.

Florian Dombois: First of all, I didn’t want to use the Research Pavilion as an opportunity to show off institutional activity. Nor did I not want to use it to represent or validate research or its outcomes. As you know, I am quite critical about research being used today to validate art. So, for example, I reduced the exhibition area/the white cube to one third of the Sala del Camino, and shifted the areas supporting the art into the room from both sides: the workshop/ studio and the discourse. The centre of the space I left empty as I wasn’t showing any artwork. My main activity concentrated on the support areas. I spent Tuesday to Friday in the workshop and Saturdays in the Palaver area discussing questions about research with invited guests. I wanted to do research; to use Venice as a lab allowing for chance. I didn’t set up something ready-made and safe like also most other pavilions. I wanted to work on-site, to use local materials and energies, to articulate from what I found. I wanted to rely on local transport, local energy, on Fortuna, who, at the Punta della Dogana, turns according to the wind. I hoped to accomplish an art work. I opted for all-out risk, for uncertainty, for discomfort. I didn’t conceive research as an academic straitjacket, but as a process, as a willingness to take risks, as something open, with an unknown outcome, as a form of not-yet art. So I planned a Galleria del Vento, which translates both as a ‘Gallery of the Wind’ and as a ‘Wind Tunnel’.4 At the beginning of the exhibition, I had a machine with artificial wind in the workshop and I opened the windows to enable the natural wind to cross my white cube. Over the next five weeks, I slowly shaped the artificial wind, while the natural wind was crossing the Sala del Camino. Fortunately, I finished the wind tunnel, i.e., turning the artificial, now-laminar flow into itself. The same day a huge storm raged for two days outside. And then came a dead calm, zero wind. That was the last day of the exhibition.

Michael Hiltbrunner: How come your research group, which helped to create the project, wasn’t mentioned, but only some multi-disciplinary students?

Florian Dombois: As I said, I didn’t want to represent the work I was doing in Zurich. My aim was to do new research. And you seemed to have missed the fact that the institution, Zurich University of the Arts (ZHsK), received prominent mention (i.e., credit) on every poster, flyer, public text, etc. I literally sailed under the flag of ZHdK (a white Z on a black background). I also had an information desk installed at the very centre of the Sala del Camino. On unmistakable display was The Wind Tunnel Model,5 a volume containing texts by all my team members about their projects, plus a shelf with copies of The Wind Tunnel Bulletin,6 which my team and I have published over the years; I also displayed a copy of Domesticated Wind, a CD produced by Kaspar König, my assistant.7 In other words, the collective that I had established was variously credited.

And you need to know a bit more about how I set up the Zurich team. In 2011, I founded the ‘Research Focus in Transdisciplinarity’ and developed the idea of a wind tunnel as its centre. In 2012, I hired Kaspar to build a wind tunnel for me. I organised the funding, wrote the research applications and initiated the intellectual discourse aimed at discussing why an art school should have a wind tunnel etc. I encouraged my team members to publish their work in their field individually, mentioning ZHdK and others merely in the acknowledgements. For instance, I encouraged Kaspar to make the CD, funded it, organised a publisher, etc. And I supported Haseeb with developing his artistic PhD, again funding his work, his shows, lectures, etc. But I never used the wind tunnel for one of my own works of art. Venice was the first time that I wanted to articulate a wind tunnel the way I think it ought to be done.

Florian Dombois & Ugo Carmeni, Venice wind tunnel, 2017.

Florian Dombois & Ugo Carmeni, Venice wind tunnel, 2017.

Ugo Carmeni, Sailboat which was used for collecting building material in the lagoon, 2017.

Ugo Carmeni, Sailboat which was used for collecting building material in the lagoon, 2017.

Florian Dombois, View into the Galleria del Vento from the info desk with book and online log of the daily travels, 2017.

Florian Dombois, View into the Galleria del Vento from the info desk with book and online log of the daily travels, 2017.

Michael Hiltbrunner: Why did you highlight the students? How could or should a student become involved in artistic research?

Florian Dombois: Yet again, talking, talking. Everybody in artistic research seems to talk. I organised housing for everybody in a palazzo instead, drummed up travel expenses, arranged for two study credit points to be awarded, and asked students whether they were prepared to work with me, physically. Every day, we sailed out to different abandoned islands in the lagoon, collecting old wood and forming with it a wind sculpture, as I like to see the wind tunnel. We did what good researchers do – we explored unknown territory, collected different kinds of material, formed something new from that material, which was subsequently even published in a professional surrounding, and engaged in discourse with our international peers.

Just compare this to the usual artistic research courses at our school, where they usually read philosophers and teach how to write footnotes or a bibliography…

Michael Hiltbrunner: Do you see this moment as an endpoint of artistic research? Have you broken with it? Or how do you want to establish a new debate, a new culture? What might the future of artistic research look at in that respect?

Florian Dombois: I don’t know. I hesitate to contribute to a future of ‘artistic research’, especially because it is now very often defined and regulated by visitors of art and not by art makers.8

Also, I’m not sure whether we will ever reclaim this word for the arts. So I avoid using the term artistic research. For me, we are at the end of the poetic power of artistic research, not though at the end of thinking about new ways of making art. I also believe that the research units at art schools can provide great opportunities for developing art — if we are smart enough to use them. So is this the end? Or is it a beginning?

1 Florian Dombois, ’Die ungezogene Tochter’ [The ill-mannered daughter], Gegenworte 26 (2011): 66.

2 Taken from the Bible, it is in German an expression for ‘utter confusion’.

3 Studio Olafur Eliasson in Berlin, http://www.olafureliasson.net/studio; Studio Jeff Koons in New York, http://www.jeffkoons.com.

4 http://www.researchpavilion.fi/galleriadelvento.

5 Florian Dombois (ed.), The Wind Tunnel Model – Transdisciplinary Encounters (Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2017).

6. Distributed by art book stores like Printed Matter, New York, or Motto, Berlin, and online on http://windtunnelbulletin.zhdk.ch

7 Kaspar König, Domesticated Wind, CD 27672, tochnit aleph 2016, http://www.tochnit-aleph.com/

8 Florian Dombois: “<FLORIAN.DOMBOIS@ZHDK.CH> KIRJOITTI 17.6.2017 12.04:”, in Jan Kaila, Anita Seppä & Henk Slager (eds.) Futures of Artistic Research – At the Intersection of Utopia, Academia and Power (Helsinki: Writings from the Academy of Fine Arts, 2017), 73-81.