Introduction – Working and not working with you,

Jessyca Hutchens, Anita Paz, Naomi Vogt, and Nina Wakeford

To cite this contribution:

Hutchens, Jessyca, Anita Paz, Naomi Vogt, and Nina Wakeford. ‘Working and not working with you,.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 4 (2021), http://www.oarplatform.com/working-working/.

In this, our fourth and final issue, Working with you, we decided that instead of our usual co-authored editorial introduction, we would each contribute our own separately authored introduction on the theme, both as an ostensible nod to collaborative research relationships and as a final subversion of our own prior adherence to editorial norms. As it has worked out, an extensive series of delays and disruptions have effected this issue in particular, leaving us feeling particularly sheepish about making introductions on behalf of ourselves and others, while making claims about the nature of working relationships that are set in motion by OAR as a project. And yet, we also couldn’t resist presenting some collective thoughts on the contributions to this issue, precisely because our performative separation as editors (our individual pieces will directly follow this one) proved to re-engage us with the stakes of this issue and the complex ways contributors have articulated relations as something greatly moved on from reductive notions of individual versus collective authorship.

Currently, in art making and practice based research, working under the rubric of the collaborative, the collective, or the participatory is frequently rhetorically celebrated but in our view, often not materially or conceptually supported in-line with the specificities demanded by new working relationships, with participation, networking, and interdisciplinary dialogue often offered as their own reward. Debates more specific to contemporary art that have centred on the aesthetic, affective, ethical, and political stakes of community engagement and artistic representations of social projects are moreover not necessarily widely applicable to the wide spectrum of collaborative acts elicited through artistic and practice based research. But rather than setting their arguments against the failure of the potential of the collaborative, this issue seems to rest on the way very particular research contexts engender certain modes of relating, and their associated processes, rituals, materials, and outcomes. They suggest our working relationships always need attentiveness, wherever they may sit within any particular scale of autonomy and heteronomy.

Several contributions to this issue reflect a growing interest on the collaborative nature of research processes that are less examined on these terms, or might usually be considered to undergird forms of creative autonomy, drawing out the subtle social and artistic exchanges that are usually in the background of more individuated projects or projections. This includes a piece by oral historian Rib Davis, presented in the form of a recorded conversation between himself and three other historians, on how interviewees shape their own narratives through the dialogic process. Marie Caffari and Johanne Mohs investigate the underexamined collaborative exchanges that take place between creative writing students and mentors/supervisors. Mihai Florea, meanwhile, progresses an examination of the anxieties of preferring lone research within a Theatre Studies department and the potentialities of performative thought processes, through a ludic collaboration with a stick. Indeed, collaborations with and between non-human actors are a major theme within this issue. Jessica Sarah Rinland’s essay expounds upon the artistic research processes that led to the creation of a ceramic replica of an elephant tusk, as a means to reflect on and replicate museum conservation practices. Johann Arens’s video work explores the intimate tactile relationship between objects being packed and sent and the customised cradles (created from foam moulds) that ensure their care and safety.

Pieces that turn more towards collaborative contemporary art production each refute reductive framings of identity-positions, such as between artist and participant, collaborator, community, or audience. The cover for this issue, by the artistic collective the Tennant Creek Brio, reflects their shifting set of artistic positions and collective formations across artworks and mediums, their practice forming a diverse mediation of issues inherent to the contexts where the artists live, work, practice culture, and resist on-going colonialism. A text by Elisabeth Lebovici, translated from French to English by Naomi Vogt, considers the role of collaborative exhibition cultures acting within the social transformations of the Lower East Side in New York during the midst of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s and early 1990s. Martina Schmuecker’s filmed performance collaborates with other artists across time, re-enacting and re-working pieces by Robert Morris and Carolee Schneemann. In a study of self-organised groups in the Netherlands, E.C. Feiss unpacks the complex mechanisms of collaboration between undocumented people and the contemporary art world.

Other works more directly grapple with artistic collaborations as participants, reflecting back on their involvements. Katherine Guinness, Charlotte Kent, and Martina Tanga reflect on a specific collaborative endeavor, a workshop titled FAAC YOUR SYLLABUS, that they ran as participants of the research group The Feminist Art and Architecture Collaborative (FAAC), pushing past the often utopian ideals of collaboration to also explore its challenges and performative aspects. Three musicians, Francois Blom, Garth Erasmus, and Esther Marié Pauw listen back and reflect on recordings of the music theatre production Khoi’npsalms, exploring its multiple meanings as a work of decolonial art, and its creation of both tensions and intimacies through collective sound-making.

Finally, in the four pieces that begin this issue, four OAR editors (Jessyca Hutchens, Nina Wakeford, Anita Paz, and Naomi Vogt) consider what it has meant to work together on this collective project, which has entailed various forms of coming together (often across four time-zones, and sometimes in shared physical space), as well as a various forms of working with contributors and institutions. We left the title of this issue as an unfinished sentence, ‘Working with you,’ because there is rarely only a singular you, but a great many you’s that form our creative working relationships. Rather than a simple valorisation or critique of the collaborative, this issue hopes to be attentive to the relations of our working lives, and the multitude of ways they produce creative work.

WORKING WITH YOU, AND YOU, AND YOU

Jessyca Hutchens

Ideas around artistic autonomy have made a comeback in recent years, largely within the context of discourse around creative labour as a model for the ideal neoliberal subject – one who is both highly individuated but also sociable, flexible, mobile, networked, and able to leverage vast horizontal social networks. On the one hand, ideas of artistic autonomy are now said to be imbedded within the professional values of neoliberalism, and its conditional promise of greater personal freedom and flexibility, while also often leading to precarious conditions and a blurring of work and social life. At the same time, theorists are still optimistic about the potential for artists to reclaim forms of autonomy away from neoliberal professional values and labour conditions.1

Fidelity to self, to one’s own ideas, to deeper relationships that exist in excess of or outside of productive relations, as well as to certain forms of rootedness, slowness, and retreat from hyper-productive environments are now often being positioned as oppositional to dominant modes of production. Papers extol the radical political potential of everything from friendship to remote artist retreats. But there is also much critique around how such forms and practices have also been long incorporated into the stop-start patterns of neoliberal work, even part of a broad imperative to self-manage: to find time, to take time-out, to retreat, to set boundaries, to re-centre, to be mindful, to find that ever elusive work-life balance.

OAR is highly exemplary of the on-going negotiations that collaborative work now so often demands. As editors we schedule and re-schedule meetings across three or four time-zones, divide and re-divide up tasks in response to our own shifting workloads and the time pressures of those we work with, we regularly type out the familiar scripts of apology and appeals for more time, another time, a better time. We make space for our friendship, and also sink into long delays and silences. We place and face pressure, retreat, and re-emerge. Instead of a regular shared time and place to work, we have only our shared commitment to a collective project to keep us going, which is itself an amorphous, highly flexible entity.

The idea of the ‘project’ has been much theorised as a particular mode of production within contemporary art, generally understood as an on-going processual way of working that tends to exacerbate the blurring of professional and personal domains. Bojana Kunst describes art projects as ‘processual, contingent and open practice’, a mode of working she argues unduly focuses on possibilities in the future at the expense of connections to social life in the present, leading to a kind of unending speculative mode of working/living.2 This way of thinking about projects has particular relevance to the paradigms of practice-based and artistic research, that place high value on open processual modes and forms of research documentation. OAR is explicitly a platform that accretes outputs from open-ended research-based projects, and itself eschews the traditional temporal modes of most journals. On the one hand, it seemed valuable to actually help give ground to some of this on-going, iterative work, which often exists through even more ephemeral formats, yet are we also contributing to work cultures that become all-consuming due to their endless deferrals?

Boris Groys has written of the loneliness of the project, due to the way projects immerse subjects in a heterogeneous time that is desynchronised from the time experienced by society.3 Groys acknowledges that while projects are often a collective effort, loneliness persists in the form of ‘shared isolation.’4 The demand (and also pleasure) of large collective projects like exhibitions, or films, or journals, is to retreat from the time pressures of ‘regular’ social life, into a more immersive and separate time-space. This notion of the project shares with traditional conceptions of artistic autonomy the idea of a separate space of creation away from the mundanity, routine, and utility of daily life and labour. Project-time is antisocial in one sense, yet also promises an intense and exciting form of sociality through a shared endeavour.

If only we could be alone together more often…

Yet, with OAR, like many other kinds of on-going projects, we only rarely step into project-time together. Most notably, we undertook a residency together at the remotely located Bibliothek Andreas Züst, spending our days balancing frantic working with long alpine walks, the ultimate form of enacting collective isolation to immerse in our project. More often though, OAR takes a backseat to the demands of other projects we’re each involved in as researchers, only asserting the heterogenous time of the project intermittently through global video calls, periods of intensive work, and our on-going sense of commitment to something that no longer has an institutional home or on-going funding. In many ways the loneliness of a single project begins to sound ideal in comparison to the variegated time of multiple, overlapping, open-ended projects.

Although strongly associated with contemporary forms of precarious labour, project-work perhaps also offers pleasures that have been eroded elsewhere, creating intimate forms of collective engagement amidst widespread social isolation and work based around competition and self-management. I often wonder in regard to OAR if we would we have stayed in such close contact as friends without the promise, excuse, demand, and energy of a collective project. Recently I made a film with my 92-year-old grandmother, a project that entailed us completely up-ending the usual routines and spaces of the house we currently share with other family, in ways that felt exciting and bonding. Is it that domestic and social life is now more subject to project-logics (do we need ‘projects’ to justify time at home?), or maybe it is more that work has long managed to co-opt something of the collective spirit of family and community life, the heterogenous time of communal ritual or the kind of community or civic projects that once committed to distant futures.

Maybe we need more communal projects that strengthen our social bonds outside of our working lives. While OAR is definitely a form of work within our respective fields, unaffiliated to any of our current places of employment, it allows for certain kinds of freedom and interruptions to our work for institutions. Maybe it is always pertinent to ask: what is a particular project interrupting to instantiate its own collective autonomy away from things? While project-work is a dominant form of labour, we should be attentive to the specific textures, demands, energies, and pleasures that different projects create. Pascal Gielen has argued that ‘autonomy can only be through heteronomy’, and also that ‘artistic autonomy does not coincide with individual discretion and exemption from collective obligations.’5 Perhaps this means finding forms of mutual support and collective passion that are generous and attentive to our lives and obligations as individuals. Autonomy, not as lone researchers within precarious institutions, but through collective arrangements that are consciously protective.

OAR has teetered on drifting away at times, becoming increasingly unmoored as we have moved to live and work in different places. Keeping it going is more than just the time-puzzle of administering collective work, it’s marshalling a kind of shifting collective energy that feels special and particular to this project and to us. I wonder now if that’s sort of what we were thinking about when we titled this issue ‘Working with you,’ an unfinished sentence that addresses a particular subject, a you, instead of focusing on particular collective forms: collaboration, participation, social engagement or so on, terms which all have their own way of reducing the nature of social/working relations down to a kind of desired product or outcome. Through OAR, I am working with you, and you, and you…

DEAR JESS, NAOMI AND ANITA

Nina Wakeford

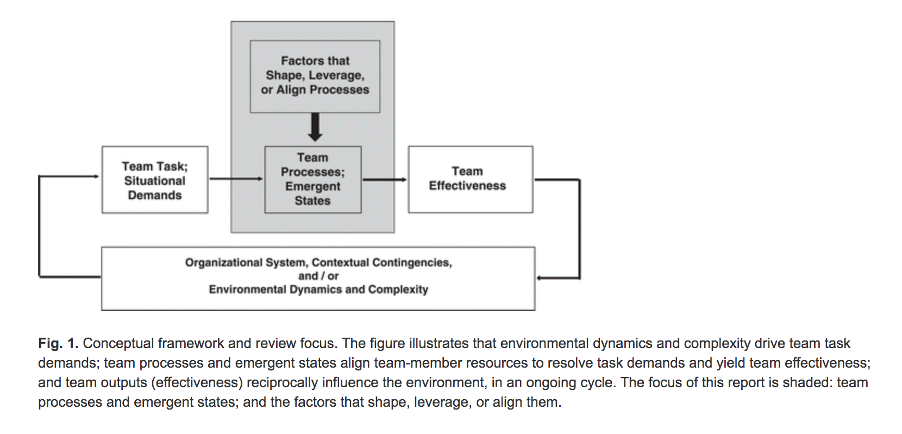

Hi there. It has been such a joy working with you, three. We have lived through many of each other’s rites of passages – educational, paid employment, domestic. I was remembering recently the afternoon we pitched our proposal to the (was it IT?) grants committee at Oxford. I recall that we were up against ‘ap developers’ and it seemed improbable that a small, fine art-led humanities project led by four DPhil students could be convincing in terms of what appeared to be criteria tipped more towards entrepreneurship or digital ‘quick wins’. What prompted me to also work with Hannah for our first issue – revisiting Adrian’s words on capture of art by academia. The University funding scheme was geared to an outcome much smaller and more discrete than this has ended up being. This morning, when we all discussed the introduction, I showed you these photos of us in the Alps. It was when we were trying to sort out the article order for one of the issues, and we cooked together in the large kitchen so generously at our disposal. (You didn’t expect me to avoid sentimentality, did you?). And then the group shot – I think another resident took this? This morning three of us agreed that we’d share them here (So I hope Anita is ok with that). I’ve followed them with a diagram I found in an article on ‘team effectiveness’ and I’d love to know what you thought an OAR version of this diagram would look like!

Figure 1: from Kozlowski, Steve W.J., and Daniel R. Ilgen. ‘Enhancing the Effectiveness of Work Groups and Teams.’ Psychological Science in the Public Interest 7, no. 3 (December 2006): 77–124.

WORKING WITH YOU,

Anita Paz

Working with you was a negotiation. Give and take. You give some thoughts; not all – some you may want to keep for later, for and to yourself. You take some thoughts; not many – after all, take too much and it’s no longer with you. At times a conquest, at others, a surrender. Working with you is working in the space between not giving too much and not taking too much. It is there that a compromise must be found. A middle line of no-one.

Working with you was a translation. An attempt to think, to talk, to write in at least four different languages, and to do so at once. Negotiating my owns for yours, and all of yours for all of mine. And at the end of that, all these different forms of expression, all these languages which are ours, condensed into a single one. Which is of no one. All the thoughts that we gave pushed into a single utterance. No longer a plurality, but a hybrid. It is ours, but it is not yours, nor is it mine.

ALONE TOGETHER WITH THEM

Naomi Vogt

From the very start, establishing OAR required mapping out all the issues we would publish, with timelines and themes. This was the lot of a hopeful project that needed a handful of hard facts to demonstrate feasibility, including when it came to convincing ourselves. Thus an editorial arc was traced with Jessyca Hutchens, Anita Paz, and Nina Wakeford: the colleagues with whom I would end up editing this journal. Working with them, in a sense, meant imagining our collaboration until its end. And building that required methods not unlike those of make-believe.

We would write and put together a prologue, which we would call issue zero. Because one of the platform’s aims was to foster forms of dialogue, citation, and response which we felt were lacking in the arts and humanities, we found a designer – Julien Mercier – who would not only make space for these features but would structure an entire platform according to them. When he finished building the site, he thought OAR would need its own typeface, so he half-secretly designed a full alphabet font and called it Oar. Everywhere around us, artistic research seemed to be proliferating without formally accreting. So we decided that any work responding to a previous output would become quotable as a response. And the timeframe to submit response proposals would be unbound. The published responses would present as horizontal reactions to a primary output. This way, pairs or clusters of publications would stand in relation to each other like shot-counter-shots in a film, rather than forcing the reactions to gather at the bottom, creating vertical hierarchies and the suggestion of increasing remoteness. On this platform, we wanted researchers and artists to be able to think, work, research, write, and produce together, whether at once or asynchronously.

Once we started working together as an editorial team, the day-to-day facts of this collaboration became as salient as the ideals at the heart of the journal. For me, the strongest realization remains – perhaps quite unspectacularly – the experience of sharing an inbox with three other people. It was unsettling at first, this decision to trust in three individuals to share my mail, to address someone I might admire, to handle prickly administration or to hold a meeting with a contributor on my behalf if needed. None of this involved the assumption that they would think or act similarly to me – sometimes quite the opposite. This shared custody of communication and email became natural in a way that still feels meaningful now. I don’t think I would want to share an inbox with anyone else, including with people whom I might know even better and whose work I trust just as much.

Of course, working with my co-editors has entailed many other events, some of which are more conducive to narrative. We spent a week in residency at an Alpine library barely sleeping to get our first issue out while the weather turned from hot sun to piles of snow overnight. We presented our work at conferences, standing for the first time in front of an audience not alone (an audience that would occasionally remark on the fact that we were a team of four women – to which we tended to answer: ‘Yes’). We had long debates on the rare occasions where a submission would receive both the highest and lowest review rating, followed by the strange experience of trying to convey why something is very bad or very good to people who – by then I had started to assume – read, watch, listen, and judge in ways that are coextensive with mine. Yet somehow the form of collaboration I still find most remarkable continues to happen mundanely via the interfaces of electronic mail systems and word processing software. I can fathom the fact that I work with them most clearly when I am able to identify which one of us has edited (or, more nerdily still, copyedited) a piece we are publishing based solely on the nature of the suggested changes.

In this issue, the two submissions that I followed are a sound work by Rib Davis and an article by E.C. Feiss. Davis led a workshop on oral history interviewing which I attended at the British Library a couple years ago. Intrigued by the course’s approach to oral history as a form of research where ‘the product is the process’, I invited Davis to submit something to OAR. He developed a project akin to a short oral history of oral history practice. The work generously weaves together three conversations between Davis and other historians. Together, they explore the ethics of their work, the benefits of simply listening, and the peculiar ways in which subjects shape the narratives of their lives by expressing them orally. Feiss’s article carefully unpacks the complex mechanisms of collaboration between undocumented people and the contemporary art world. Her research here focuses on We Are Here (WAH), a self-organised group of undocumented people based in the Netherlands. The text considers another group’s practice, called Here To Support, which quietly orchestrated the insertion of WAH into the Dutch art system. Simultaneously emerging from Feiss’s article is an analysis of the ubiquitous incorporation of refugees into contemporary art.

My role in a third contribution to this issue was more involved. I translated to English the text by Elisabeth Lebovici ‘Exposer, montrer, démontrer, informer, offrir’, which was first published in 2017 in her book Ce que le sida m’a fait – Art et activisme à la fin du XXème siècle, but which partly originated in 1983 as a chapter of her doctoral thesis. In this text, the city of New York and particularly the Lower East Side is connected with the transformation of contemporary art exhibitions. In the 1980s and early 90s, HIV/AIDS provoked panic and silence. At that time, collaborative exhibitions – which Lebovici experienced and participated in directly – created time and space for the epidemic’s political visibility.

Translation work is how I funded most of my life as an undergraduate. I started by working for a search engine dedicated to design products, and was later hired by a film festival. Only very rarely did I translate texts written by an identifiable person. This time things were different – I specifically wanted to translate something written by Lebovici. I had admired her work and read her art criticism when I lived in France. Her focus on queer histories and feminism was in many ways the diametrical opposite of the art history I was studying at the Sorbonne, as was the seminar ‘Something You Should Know’ which she has co-convened with the EHESS for fifteen years. I was excited to help translate a small piece of this world into English. And I enjoyed doing it partly while living in New York, walking through streets whose existence was differently vivid in Lebovici’s text. I liked imagining this text reaching a wider Anglophone or polyglot readership, since English of course also holds this dubious role of lingua franca.

Describing the collaborative work of translation is delicate. This is in part because my theoretical understanding of it is limited. I attended a translation study day once. In the French-to-English seminar I chose, we looked at Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le petit prince (The Little Prince), pausing on a famous passage in which the little prince asks the narrator: ‘S’il vous plaît… dessine-moi un mouton!’ (‘Please… draw me a sheep!’). We discussed the impossibility of conveying the French sentence’s cherished strangeness which results from the child’s mixed use of ‘vous’ – the polite form – and ‘tu’ via the imperative ‘dessine’ – the informal form – in a story that is all about making friends via taming animals and people. It came up that certain translations had later opted for the English sentence: ‘Please… draw me a lamb!’. Since the connotation of innocence stemming from the French bumbling conjugations was untranslatable, it was the animal in the sentence who, instead, had been rejuvenated and made tenderly inexperienced.

This philosophy of the lamb is what I turn to every time I am stuck in translation. Most of the time translation can indeed feel both lonely and too crowded – a constant tug between faithfulness to and emancipation from the original author, who often becomes an imaginary interlocutor. Other voices intervene too. Here, author Adrian Rifkin kindly read my translation, and my mother Barbara Vogt, who taught English as a second language in high schools, read the text during its translation. Yet in this case I was also lucky to find a generous and responsive real interlocutor in Lebovici. I wondered if I had undertaken a translation as an act of scholarly fandom. But by the end what mattered was how this text taught me to work with even more people than before. There was the researcher and writer of 2017 who had written the chapter; the emerging art historian who had experienced the matter first-hand in the 1980s and had later lost to AIDS friends she made at the time; and the embodied author and reader of my translation in 2019-2020 (namely all three Elisabeths), as well as, from the start, my co-editors as readers, and myself as a translator, collaborating alone, together with them all.

1 For example see Pascal Gielen, Mobile Autonomy: Exercises in Artists’ Self-Organization (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2015).

2 Bojana Kunst, ‘The Project Horizon: On the Temporality of Making,’ Maska, Performing Arts Journal 27 (2012): 149–50.

3 Boris Groys, Going Public, 1st edition (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2011), 70–84.

4 Ibid.

5 Op.cit., Paschal Gielen, p. 78–9.